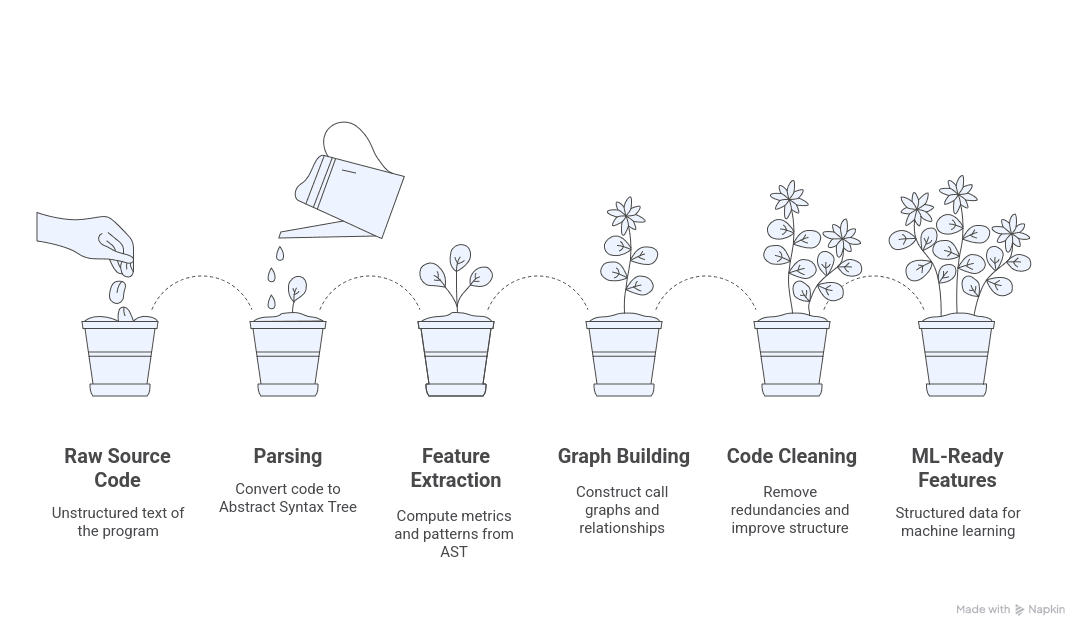

to analyze source code with machine learning, the first step is to turn raw text into structured data. We parse code into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST), a hierarchical representation where each node is a language construct (loop, assignment, function, etc.). An AST abstracts away punctuation and captures the semantic structure: for example, nodes can represent a function return type or a conditional block. Modern parsers like Tree-sitter support 40+ languages, so this pipeline applies broadly (Java, Python, JavaScript, etc.). Once we have an AST, we can compute metrics and patterns, build graphs (e.g. call graphs), and clean the code — all of which feed into ML models as features. The sections below cover each step in depth.

AST Parsing Fundamentals

We begin by parsing code into an AST.For instance, the Euclidean algorithm code above is parsed into a tree: the root is a statement sequencecontaining a while loop and a return . Each node has a type (e.g. “WhileStmt”, “IfStmt”, “BinaryOp”)indicating its role . ASTs omit trivial syntax (like parentheses or semicolons) and retain only the structure. In practice, a parser tokenizes the code and then builds this tree . Unlike text-based analysis,AST parsing is language-aware: it lets us ask questions like “which functions call this one?” or “what type

does this variable have?” by traversing the tree, rather than relying on brittle regexes .

Tools like Tree-sitter can even handle incomplete or erroneous code via error recovery, producing a valid AST despite syntax errors . This makes the pipeline robust to code being edited or partially written.ecause ASTs explicitly show loops, branches, function declarations, etc., they form the foundation for extracting features: all subsequent analysis works from this tree representation.

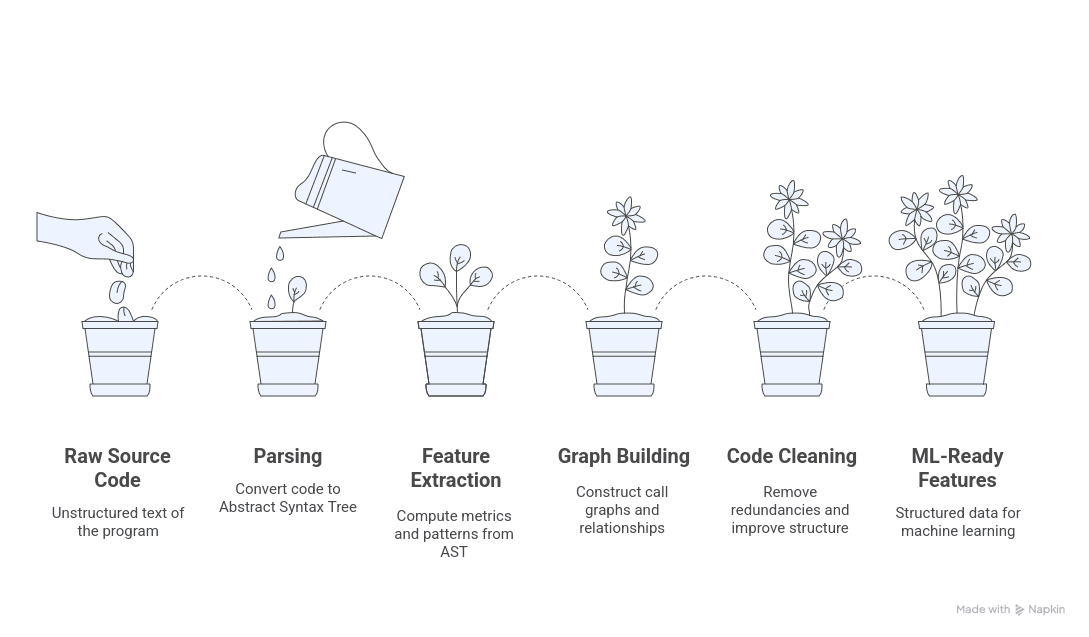

Feature Extraction Pipeline

Once we have an AST, we extract quantitative features in a pipeline. Key steps include:

*Code complexity metrics: Compute numeric metrics by analyzing the AST (and sometimes control-

flow). Common ones are Cyclomatic Complexity (McCabe’s metric, counting independent paths in

the CFG) and Halstead measures (based on operators/operands) . For example, Cyclomatic

Complexity is defined as the number of linearly independent paths through the code (computed as

E–N+P on the control-flow graph) . Halstead’s Volume is calculated as N log₂n, where N is program

length (total operators+operands) and n is the vocabulary size (distinct operators and operands) .

These metrics quantify how intricate or large a code block is. We also compute simple size metrics

like Lines of Code (LOC) — the count of executable lines excluding comments/blanks — and object-oriented metrics like coupling

*AST structural features: Extract counts or patterns of specific AST nodes. For instance, count the

number of loops, conditional statements, function calls, or nesting depth. We can also detect known

code patterns or idioms by matching subtrees. Because an AST represents structure, design

patterns or code idioms appear as characteristic shapes: “the AST lets us recognize coding patterns

structurally rather than textually” . For example, a builder or singleton pattern will have the same

AST shape regardless of variable names. We encode such patterns as features (e.g. binary flags or

counts).

*Basic code metrics: Record other simple metrics from the AST or tokens: total number of functions/classes, number of variables, fraction of commented lines, etc. For example, LOC (lines of executable code) is a basic size metric . Depth of inheritance or coupling measures (number of cross-module imports) can also be extracted from the AST. Although LOC was mentioned above, here we treat it as one of several size/coupling features: e.g. “number of methods” or “comment density.”

In practice we implement this pipeline as follows: parse each source file into an AST, then walk the tree (recursively) to compute metrics and gather patterns. This might be done with language-specific libraries (e.g., Python’s ast module, or Java’s Spoon), or with multi-language frameworks like Tree-sitter. The output is a feature table: one row per code unit (function, file, or project) with columns for each extracted metric or pattern count. These features become the input to ML models

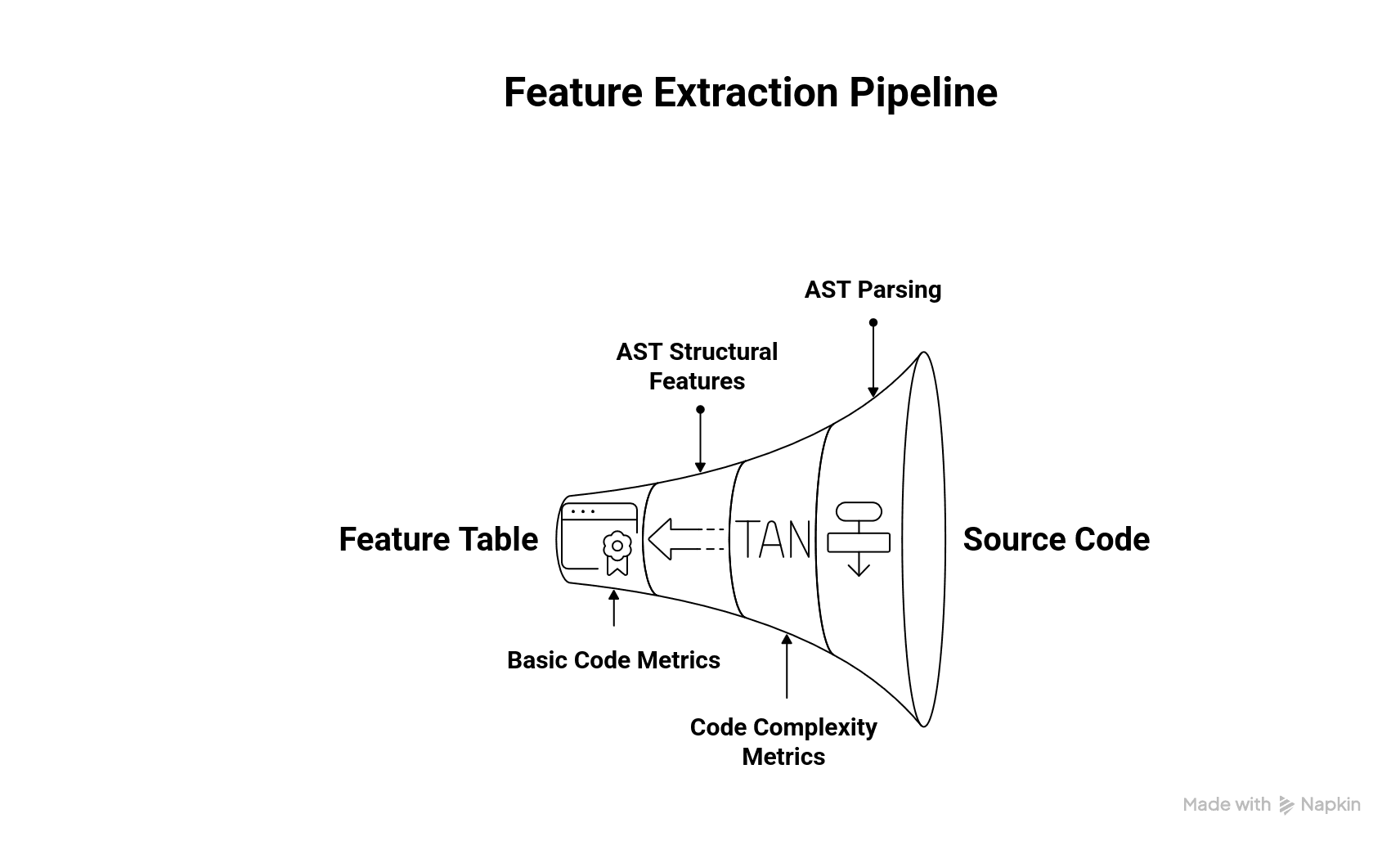

Graph-based Code Representation

Besides pure AST features, code can be represented as a graph to capture elationships. A simple example is a call graph: nodes represent functions (or methods) and directed edges indicate “A calls B”. The figure below shows an example static call graph

A call graph is “a graphical representation of the relationships between different function calls” . In the diagram above, the main function (red node on the left) calls three subprograms ( Ejercicio1.mainExec , etc., blue nodes), each of which in turn calls showDescription (red node on the right). Building such graphs helps analyze cross-file and inter-procedural structure. We can construct these graphs by traversing the AST (or bytecode): for every function call node, add an edge in a networkx graph object. Once built, network analysis yields new features: for example, node degree or centrality can quantify how “important” a function is in the codebase.

More generally, advanced code analysis uses Code Property Graphs (CPG), which merge several layers into one graph . A CPG includes the AST structure plus edges for control flow (CFG) and data flow (DFG), forming a single “super-graph” . This graph contains almost all information needed for static analysis (AST nodes, control dependencies, data dependencies) in one place. Tools like Joern generate CPGs and

store them in graph databases for powerful queries. Even without full CPGs, using NetworkX to represent ASTs or CFGs allows computing graph features (e.g. connected components, graph diameter) for ML. For example, the codegraph-fmt library automates this: it parses Python code into ASTs and saves them as annotated NetworkX graphs with custom node/edge features . In summary, graph-based representations capture program-wide relationships that isolated AST features might miss.

Code Preprocessing and Cleaning Techniques

Before feature extraction, we often clean and normalize the code. Common steps include removing or normalizing comments and whitespace (so that analyses ignore irrelevant text), and unifying code style (e.g.running a formatter like Black for Python or Prettier for JS). Non-functional code (debug printouts,commented-out blocks) can be filtered out. For some tasks we even anonymize identifiers: e.g. replace all variable names with generic tokens ( var1 , var2 ) to focus on structure. Crucially, real-world code can have syntax errors or be incomplete (during development). Parsers like Tree-sitter are robust to this: they perform error recovery, meaning they can often generate a useful AST even if the code has mistakes .(This makes continuous analysis possible while code is being edited.) The net result of preprocessing is a clean, normalized AST (or code token stream) that better highlights the essential structure for downstream analysis.

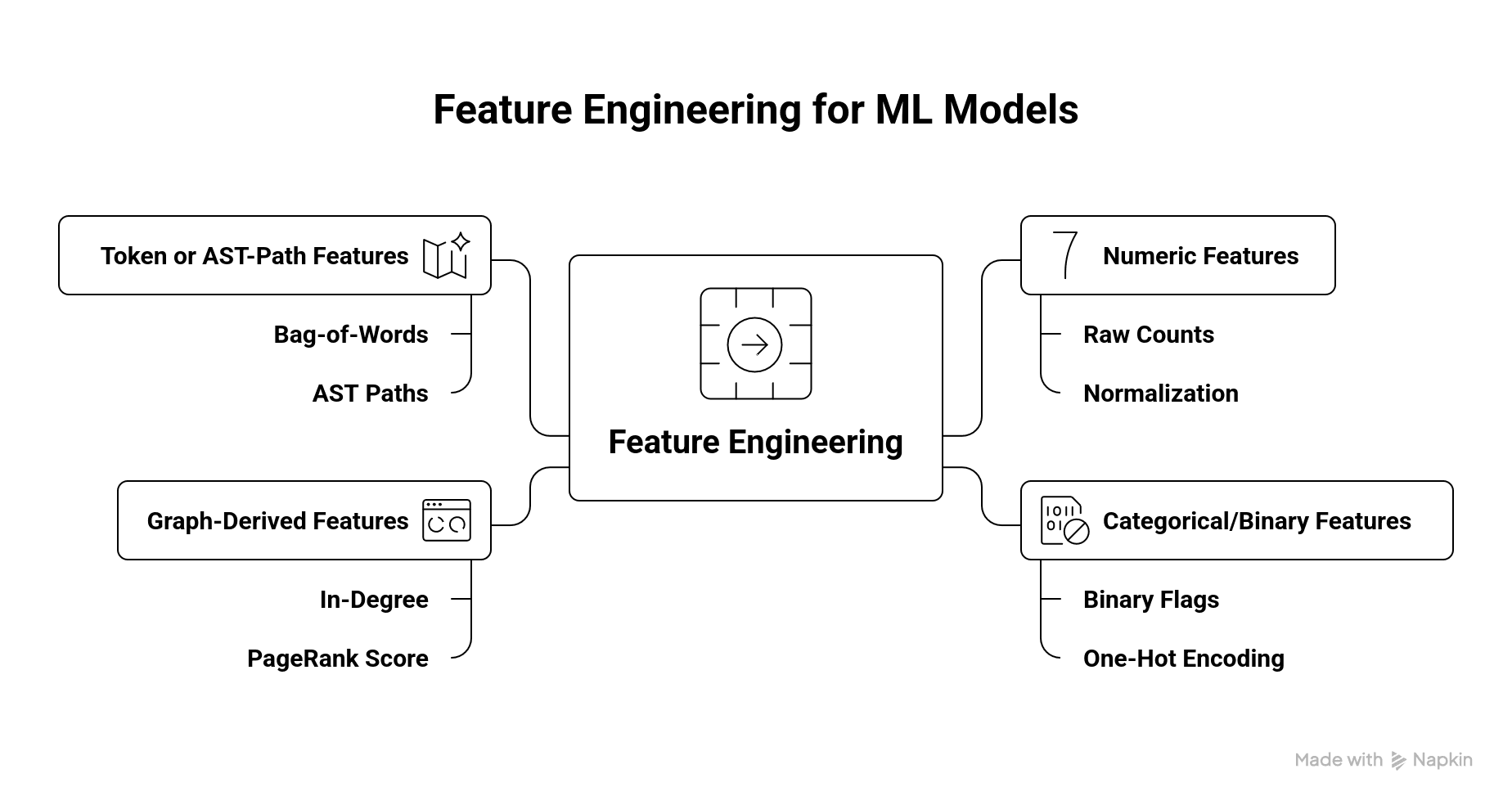

Feature Engineering for ML Models

The extracted data must be turned into model-ready features. In practice we assemble numeric vectors from our metrics and patterns. Key considerations include scaling, encoding, and dimensionality:

Numeric features: Raw counts (e.g. LOC, cyclomatic complexity) are typically used directly or normalized (e.g. z-score). For example, if using cyclomatic complexity and Halstead volume as features, we simply feed their numeric values into the model (possibly after log-transforming large values). These continuous features capture size and complexity of code segments .

Categorical/binary features: Many structural properties become categorical features. For instance,“contains recursion” or “uses try-catch blocks” can be binary flags. Design patterns or code idioms detected in the AST (as discussed above) become binary or count features (e.g. “BuilderPatternPresent = 1”). We typically one-hot encode such features or simply use 0/1 columns.

Graph-derived features: If using a graph representation, we include graph metrics as features. For example, in a call graph one could include each function’s in-degree (how many callers it has) or PageRank score. NetworkX makes these computations easy. These features capture the “role” of code components in the overall program graph.

Token or AST-path features: For richer semantic encoding, we can embed code contexts. One approach is to treat code as text (bag-of-words on identifiers/operators). A more structured approach (as in models like code2vec or code2seq) is to extract AST paths: for each pair of leaf nodes in the AST, record the sequence of node types connecting them. These paths form a “bag of path- contexts” that can be vectorized . In code2vec, each such path (plus the two leaf tokens) is mapped to an embedding, and the embeddings are combined by a neural network. The key point is that structural AST information can be encoded as learned features.

After feature extraction, we typically split the data into training/validation sets. We may perform feature selection or dimensionality reduction (e.g. remove highly correlated metrics, use PCA, etc.) to improve model performance. The final feature matrix can then be fed into ML models (classification, regression, etc.)

for tasks like defect prediction or code quality scoring. Throughout, careful feature engineering (e.g. normalizing scales, handling skewed distributions) and validation (to avoid overfitting) are crucial for good results.